JURORS HAVE CHANGED -Juror strategies for the new age

I rarely publish material from other trial information sources. I also rarely post anything that is lengthy. However, when I read the following article from the Washington State Association for Justice Trial News I was struck by the accuracy of the advice about today’s jurors and jury selection. I’ve known Jeffery Boyd and Deborah Nelson, fellow plaintiff lawyers, for years. They have a trial practice and also offer trial consulting as Boyd Trial Consulting. I think you will benefit from their article which they have given me permission to reprint here.

JURORS HAVE CHANGED:

Pandemic-Era Trial Lessons and Juror-Centric Strategies for the New Age by Jeffrey D. Boyd, Esq.Deborah M. Nelson, Esq

People are WORN OUT – years of divisive politics, an international pandemic, and now a war.

- People are AFRAID – will the sand stop shifting, and where will I be when/if it does?

- People are STRETCHED – illness and loss, hard decisions about childcare and school safety, elderly parent care, trying to stay healthy, worry about keeping food on the table, supply chain issues, labor issues . . . how will I hold it together?

HOW WOULD YOU LIKE IT IF. . .?

Given the above, how would you like it if I told you that you were going to receive a Jury Summons today that would require you to go to your county courthouse every day for the next two weeks and listen to a bunch of scientists debate physics, after which you’d have to vote on which direction to point the James Webb telescope?

What would you say? “I’m busy. I have a family. If I don’t work, I don’t get paid. Why is this my problem? What do I know about the James Webb telescope? Can’t somebody else figure this out?” And, for some jurors, after being sequestered at home for two years, the prospect of being present in person in an unfamiliar setting is surprisingly daunting.

Jurors understand the James Webb telescope better than they understand “proximate cause.” Our battles are not their battles – until jurors understand what’s in it for them. To win at trial, you have to make the jury feel that what they’re doing is worth their time and their emotional energy.

JUROR-CENTRIC STRATEGY, LEVEL 1: PRESENTING YOUR INFORMATION – MESSAGING AND TECHNIQUES – the “BEs”

Meeting the needs of COVID-era jurors is more work up front, but substantially less work during the trial. You’re going to need to be more focused, you’re going to need to take less time, and you’re going to need to have visuals for everything that is important.

It’s a swarm of “BEs”:

- Be Simple

- Be Brief

- Be Clear

- Be Visual

- Repeat

BE SIMPLE: SIMPLE = STRONG

Don’t over-try your case. There are only a few things in any case that matter. It is 100% certain that complexity favors the defense. When people are mentally exhausted, they fall back onto the biases they had when they walked in the door. You don’t want that.

COVID has left us tired, short-tempered, with a shorter attention span, and generally scared of what the future may hold. We have been preoccupied with disease, captive in our own homes, leading a dismal lifestyle, subjected to horrendous politics, and fearing a bad economy. “I have no time to listen to your complexity.” This is no time to teach algebra.

We have no data to back this up, but we think most people’s brains are (still) running at about 60% of their normal capacity for external events. NO ONE is going to figure your case out for you. The level of information that people are going to listen to is “1 + 1 = 2” or “Bad choices + no training = harm.” That’s all they’ve got the time or attention span for. The good news is that is all you need, if your message is righteous.

BE BRIEF

NO ONE is going to pay attention to ANYTHING for more than 20 minutes. Period. “I have too much on my mind, for you to keep me here for a 3-hour direct exam of some economics professor.” If you spend a week on your half of a car crash case, by the 5th day, the jurors will hate you. They will make sure you lose. Given the challenges of the past two years, you should assume that the attention span that will (or can be) devoted to your case by disinterested jurors will be half that, if you’re lucky.

BE CLEAR

Blah, blah, blah, “negligence,” blah blah, blah, “proximate cause,” blah, blah, blah, “standard of care.” WHAT ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT?

If you can’t explain your case so a 10th grader can understand it, you’re not being clear. If you’re not being clear, you will lose. A great trial lawyer we know said he tries to never use a word in trial that he didn’t use in high school. He wins a lot.

BE VISUAL

These days, NO ONE is going to remember ANYTHING that is not reinforced with a visual aid. Here’s what they will remember: whatever you put on the screen. Control the visuals, control the case.

Use visuals at trial for all important facts and concepts. Cognitive research has shown that people process information in this order:

(1) color

(2) pictures

(3) shape and symbol

(4) printed word

(5) spoken word

But what do lawyers use most often? Number 5. Nowhere in a juror’s life are they asked to absorb important information based on lectures (opening and closing) and question-and-answer sessions that they do not participate in (direct and cross) without extensive visual support. Give it to them. Simple timelines. Pictures and diagrams. Even just an outline of who the key witnesses are and what they are going to talk about, with a headshot picture to introduce/remind the jurors who these people are. You can never have too many visuals. People ask us, “Do I have to prepare visuals for everything?” Our answer – “only for the things you want the jurors to understand, adopt, and remember.”

REPEAT

- We are preoccupied with disease, a dismal lifestyle, child and elderly parent care, horrendous politics, and a bad economy.

- NO ONE is going to pay attention to ANYTHING for more than 20 minutes (if you’re lucky).

- Most people’s brains are running at about 60% of capacity for external things.

- NO ONE is going to remember ANYTHING that is not reinforced with a visual aid.

- And NO ONE is going to remember ANYTHING the 1st time around.

Think about this: Why are “top 10” songs in the top 10? What do nearly all top 10 songs have in common? The answer is: they feature a chorus of a few words that are repeated over and over and over. And over. And over.

In the hit song “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” by Taylor Swift (which set the record for the fastest-selling digital single by a female artist in Billboard chart history), the phrase “we are never, ever getting back together” is repeated 10 times in less than 3 minutes (as is “ooh, ooh, ooh,” if you are counting . . . ). For the older crowd: “We Will, We Will Rock You!” Do you hear the music in your head? Do you want to be Taylor Swift or the James Webb lecturer? Which message are you going to remember? Which one do the jurors already know? Make your case theme a chorus that the jury will be singing to themselves in deliberations, and you will have gone a long way toward winning.

BUT THAT’S ALL LEVEL 1 THINKING. YOU WIN AT LEVEL 2.

JUROR-CENTRIC THINKING, LEVEL 2: MEETING THE NEEDS OF JURORS

THE “BIG 4”

In every single case, whether it is at the intake stage, at the discovery stage, for focus groups, or during trial preparation, we ask the following Big 4 Questions:

1. What did the defendant do wrong?

2. Why was it wrong/who says it was wrong?

3. What was the alternative – what should the defendant have done?

4. What difference did it make?

1. What did the defendant do wrong?

Jurors don’t care how badly a plaintiff is injured unless they accept that those injuries are the result of behavior by the defendant that they judge as unacceptable. Tell the jurors what the defendant did wrong by proving facts that the jurors will judge as morally wrong.

What did the defendant do wrong?

- “The Defendant was negligent.” No, that’s not a fact, that’s a conclusion.

- “The Defendant rear-ended the plaintiff.” Maybe, but that can happen (at least in the minds of many jurors) in the absence of negligence (“it was just an accident”).

- “The Defendant chose to drive so fast that when he needed to stop, he couldn’t.” (Now you are getting there, but this is better . . .)

- “The Defendant chose to drive so fast that when the plaintiff did what everyone else did and stopped for traffic, the defendant couldn’t stop and crashed into her.”

2. Why was what the defendant did wrong/who says it was wrong?

This question applies moral judgment to the facts. The defendant chose to drive at a certain speed; why was it wrong to drive that speed?

The answer to this has two components: internal validation and/or external validation. Internal validation is where the juror already believes that the defendant’s behavior is wrong. You don’t have to teach it; it is already in their heads (example – a driver must stop at a stop sign). This is the most powerful kind of validation; it is hard to change jurors’ beliefs about what is right or wrong.

External validation comes from the testimony of others, usually experts, either (1) confirming that yes, what jurors think is the rule is actually the rule, or (2) explaining the rules for things that jurors don’t know about (example – the standards for when a CAT scan should be taken when a person goes to the emergency room). Both kinds of validation must be credible and reasonable and easy to understand.

3. What was the alternative – what should the defendant have done?

Always explain clearly and simply what better choices the defendant should have made. To be a winner, the alternative has to be something that was within the defendant’s power to do and would have been easy to do. You want the jury to believe that what the plaintiff did was normal, but what the defendant did was abnormal. Ideally, your alternative is something that a juror projects that they would have done if faced with that situation.

4. What difference did it make?

This is proximate cause, without using those words (“proximate cause” is the least-understood phrase in the jury instructions, and what jurors don’t understand usually comes back to hurt the plaintiff.

Here is your chance to make a straight-line connection between the defendant’s bad choices and the plaintiff’s harms and losses. “If defendant hospital would have done the CT scan, they would have seen the plaintiff’s brain was bleeding, and could have done surgery that has a 97% success rate.” People abhor tragedy. Tell the jury how this could have turned out better, but for the bad choices of the defendant.

“WHY?”

Lawyers are great at what happened. But jurors want to know why it happened. A truck rear-ends a car on a dark and stormy night. To lawyers, negligence per se! We’re done here! But to jurors, “accidents happen.” (And, if you refer to the collision as “an accident” you reinforce the jurors’ belief that some things happen for which no compensation is due.)

The “what” – the fact of hitting someone from behind – isn’t enough. Jurors say “There are lots of reasons you might rear-end someone. They want to know the “why.” “Why” is necessary to understand the degree of moral fault that is the basis for the damages assessment.

Many prospective jurors say they don’t believe in compensation for pain and suffering. But when you push a little, you find their belief is not absolute, but conditional. If you ask, “You mean that if I caused you intense pain, you would not think I should have to pay you for that?” the reply is almost always “Well, tell me how you caused the pain? Was it an accident? Did you mean to do it? Were you drunk?” This response shows they are not really opposed to the idea of non-economic damages, they just see those damages through the lens of the moral fault that caused the injury. They’re looking for a villain, someone who behaved differently than they would have under the same circumstances. Jurors need to see that damages right a wrong, not fill a pocket. If you understand that, you can tailor your message to meet that need.

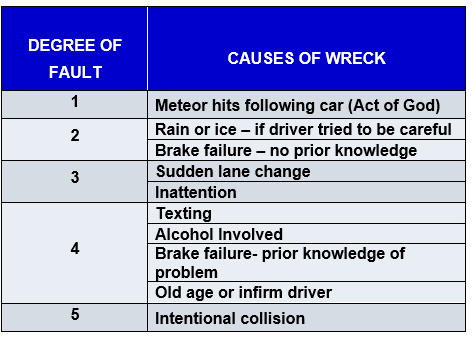

We have asked many focus groups to think about fault in all types of claims, but the most common type of car wreck claim – a rear-end collision – is illustrative. There are many, many reasons that one car hits another, and we ask the jurors to list all the possible reasons. We then ask them to sort those causes by the degree of fault they associate with them, and rank them on a scale of 1 (no or very little fault) to 5 (the highest fault). The results look something like this:

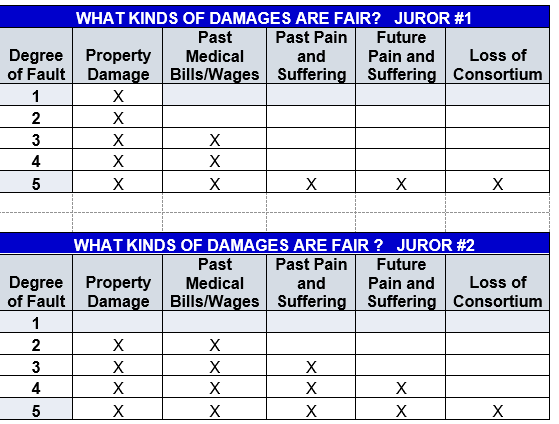

A lawyer would look at this and say, “Great! I win on 4 out of 5 of those!” and would expect a verdict including all categories of compensatory damages for any fault that is #2 or higher. The reality is different. In most jurors’ minds, not all damages are created equal. They think of the types of damages as a hierarchy. The range goes from the easy-to-understand and measure (the cost of repairs of the vehicle) up through the esoteric and philosophical (e.g. future pain and suffering, or the monetary value of the loss of consortium of a child).

Jurors award types of damages based on the degree of the fault of the defendant, not on the severity of the injury or loss. Put another way, what type of damages they think are fair depends on how “bad” the conduct of the defendant was (and how that degree of fault compares to the plaintiff’s degree of fault). For our rear-end collision example, this is what many think is fair:

This is not what you were taught in law school. The differences between the results for Juror #1 and Juror #2 are that the first juror was told the rear end collision was caused by the defendant driver’s inattention, while the second juror was told that the rear end collision occurred because the defendant driver was texting. The property damage, medical treatment, and injuries were the same for each collision; the only difference was the degree of “moral fault.” The defendant driver in the second scenario was “clearly wrong” and the cause of the collision was their choice to do something that was morally wrong, which most jurors see as a departure from their own behavior (“I might cause a collision by accident, but I would never text and drive”).

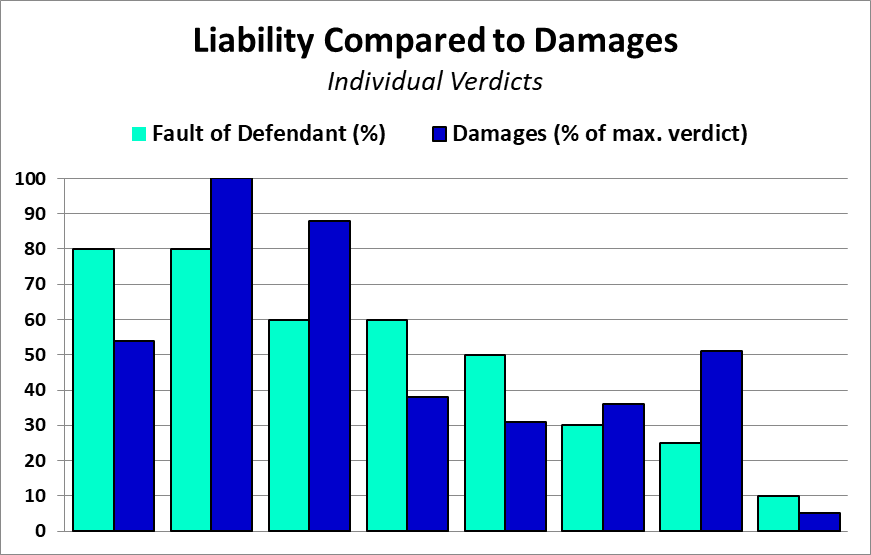

The continuum effect continues into the evaluation of the amount of damages, too. Any juror will tell you that they want to award a fair amount for damages. The problem is that they don’t really decide what an injury is worth, they decide what the defendant’s moral fault is worth. The graph below charts the results of a focus group in a product liability case. It is typical of the relationship between how jurors see fault and how they evaluate damages. Although the primary injury was objective (a below-the-elbow amputation), the assessment of damages strongly tracked the perception of fault. Result – a strong correlation between fault and damages.

LEGALLY IRRELEVANT FACTS

“What color was the car that ran the stop sign?” asks the juror. What difference does that make, wonders the lawyer. But remember – it is their trial, not yours. If it is important to the jury, it is important. Pay attention to the parts of your case that we call “Legally Irrelevant Facts.” Focus groups are particularly good at exposing what “real people” (i.e., not lawyers, their staff, or their friends and family) think is important about your case, or put more simply, what resonates with them and what they understand and remember. Here is a real example from a focus group:

The plaintiff is a well-educated, well-paid woman in her late 50’s who slipped on a puddle of water near a freezer case in a large grocery store. Through discovery, her lawyer obtained a photo that showed a water soil mark on the floor tile. In addition, the plaintiff testified that when she went to a cashier to report that she had fallen, the cashier pulled off a piece of cash register tape and said “here, just write your name on this” (as opposed to giving her an official form to fill out or calling a manager.

During the deliberations, two things came forward that surprised us. First, the jurors jumped on the photo of the long-term water mark. Of course, the lawyers in the room were thinking “See – the store had ‘notice’ of the hazard.” But the jurors, who are notoriously suspicious of grocery store slip and fall cases, said “That photo tells me that the grocery store doesn’t keep the frozen food chilled properly and that means that I’m at risk because maybe I’ll buy food that hasn’t been frozen properly and my family will be harmed.” Wait?! What?!!! Don’t fight it; this is a gift. With that information, the theme for this case became “safety” with a focus about how the store as a whole was unsafe, not just the one spot where the plaintiff fell.

During the deliberations portion on damages, one young man quickly gave us a dollar figure for the plaintiff’s damages. We pushed him a bit on “Why that number?” “What was it about that number that felt right to you?” He still couldn’t tell us, but after pushing a bit harder, he finally blurted out “Well, they didn’t respect her. When she told them she fell, they didn’t care about her, they didn’t call a manager, they just handed her a scrap of paper. I didn’t like that at all – and that is why I picked my number.” Not a word about her wage loss, nothing about her medical care, no consideration of the permanence of her injuries. It all boiled down to “respect” for this juror. And he wasn’t alone, because when we asked the jurors at the beginning of the focus group what they thought about this grocery store chain and what they expected from the corporation when they shopped there, several of them said “I want them to care about me” and “I want them to respect me.” Wait? What?!! A grocery store?! Again, don’t fight it. Use it.

After this focus group, the themes of “respect” “caring” and “safety” took center stage. The cash register tape was no longer a “Legally Irrelevant Fact,” it was evidence that this grocery store didn’t care about or respect its customers, just like the photo of the tile became evidence of a larger, more threatening danger to the jurors and to others in the store.

What are the Legally Irrelevant Facts in your case? Can you spot them? And what do you do with them? Our theory is that these are the factors that the jurors do understand – on a subconscious level. They’re easy for the jurors to spot, they are “code” for something else, and they matter to the jurors.

“THE WORLD I WANT TO LIVE IN”

What are Q-Anon followers and anti-vaxxers telling us about the world? Why do people want to believe the impossible?

In early December 2021, the U.S. had recorded more than 49.5 million coronavirus cases, and more than 731,200 people had died. Yet there was still a significant percentage of the population who refused to be vaccinated, and a not insignificant percentage that “didn’t believe” in COVID.

On November 2, 2021, hundreds of people assembled at Dealey Plaza in Dallas. They believed that John F. Kennedy Jr., a Democrat who has been dead for over 20 years, would appear at the spot where his father had been murdered in 1963 and “reinstate” Donald Trump, as President. There is video – this really happened. Why would anyone choose to believe this impossible scenario? What do they gain by embracing that belief?

Look at the comments by “Juror #9” from a recent focus group, when asked what’s on his mind: “If I go on Pandora and listen to music, the State of Washington comes on with the nurse telling me how safe the [COVID] injections are. Even though 21,000 people died [from vaccines], and we see that people are falling dead – the greatest athletes in the world in the middle of their athletic games are falling over dead. We got pilots falling out of the sky – they’re dead – you don’t dare ride an airplane that has had an injected pilot.

So, this has been an attack by the Democrats, by Fauci, by the globalists that take over our country. And it’s coming to an end, and we’re going to live through it, and we’re going to be victorious, and 97% of the corrupt criminal elite in this country are going to be imprisoned, tried, and shot. And I’m looking forward to that.”

Would it surprise you to know that Juror #9 is a 50+ year old white male who used to have a good job but who now delivers take-out meals for UBER Eats? The world isn’t working for him. And what about this:

“The minute they hand you that vaccine passport, every right that you have is transformed into a privilege contingent upon your obedience to arbitrary government dictates. . . It will make you a slave.” Would it surprise you to know that the speaker here is Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. at a recent address in D.C.?

It’s easy to believe whatever you want – whatever you want to believe, there will be a thousand Internet sites to support that belief. The question that matters – that you can tap into at trial – is “what purpose is served by that belief?” “Why does someone want to believe something that seems (to me) to be impossible?” “Why are they more comfortable believing that masks don’t work than putting on a mask – in what way does wearing a mask threaten them?”

People follow conspiracy theories or deny the undeniable because it is more comfortable to ignore facts or to believe the conspiracy than it is to deal with reality. Some people just can’t accept a world where they have worked hard and lived a righteous life that might be wiped out by an invisible virus they can’t control. Those people will change the facts to fit their beliefs. At the core, this can be unpleasant: white people who don’t like that minorities are “getting ahead” of them, less-educated resenting the more-educated. People resent those who change and grow. It’s easier to lash out than to adapt, because lashing out doesn’t require the lasher to change.

A lot of people aren’t living in the world they want to live in. They are mad. They are afraid. They are disgusted by the change they see coming. However, great plaintiff’s verdicts are driven by: FEAR, ANGER, & DISGUST. FEAR it will happen to them, ANGER because somebody didn’t do their job, endangering us all, DISGUST because someone didn’t use common sense. Direct that anger toward the conduct of the defendant!

“AM I BETTER OFF IF THE PLAINTIFF WINS OR IF THE DEFENDANT WINS?” A juror’s self-interest is a huge factor and, I believe, a prime driver behind verdicts. Jurors can’t help but see the results of the case as having an effect on their lives; they are

filtering the case through the question “Will it be better for me if the plaintiff wins, or will it be better for me if the defendant wins?” This is most easily seen in medical negligence cases, where jurors weigh concerns that a plaintiff’s verdict will raise their medical bills or make it harder for them to access medical care versus the principal that holding bad doctors accountable will increase the quality of their care. This weighing of personal interests is in the background in every case.

Also important is “system failures.” Not only was the truck driver negligent, but more importantly, the policy of the trucking company was negligent. One sleepy driver can be forgiven, but a policy that results in sleepy drivers being put on the road is a threat to each juror.

Make it clear that what’s at stake is the jurors’ world: safer products for them, the moral comfort of enforcing safety rules on a bad actor, the idea that they have a voice in how the world works, the idea that voting for you will be just – and they can be a part of that. Jurors have to decide that if they don’t vote against the defendant, the conduct will happen again, and that they or someone they love will be harmed. If they believe that, they will vote against that conduct, and “send a message[1]” sufficient to stop it from happening again.

CONCLUSION

The world has changed. What we believed to be true pre-COVID and pre-political upheaval is outdated. Prepare to meet the needs of jurors in this new age!

BONUS

The following are some of our favorite books:

- Ariely, Dan – Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions

- Hetherington, Marc & Weiler, Jonathan – Prius or Pickup: How the Answers to Four Simple Questions Explain America’s Great Divide

- McRaney, David – You Are Not So Smart [see www.boydtrialconsulting.com for a blog article about the application of this book to jury trials]

- Miller, Donald – Building a Storybrand: Clarify Your Message So Customers Will Listen [this is a marketing book, but see www.boydtrialconsulting.com for a blog article about applying these principles to jury trials]

- Sexton, Jared Yates – The Man They Wanted Me to Be: Toxic Masculinity and a Crisis of Our Own Making

[1] It’s true: as (Washington) lawyers we can’t say “send a message,” but we hear that phrase all the time from jurors in focus groups. That’s how they think; there is an element of punishment in compensatory damages awards if the defendant’s moral fault warrants it.

Jeff Boyd and Deborah Nelson are partners in the Seattle-based law firm, Nelson Boyd Attorneys, and Boyd Trial Consulting. They focus their law practice on plaintiff’s personal injury, insurance coverage and bad faith litigation, and legal malpractice. They provide trial consulting services throughout the US on a wide variety of civil and criminal cases. Deborah is a past President of the Washington State Association for Justice. Jeff is a WSAJ Board member, recipient of WSAJ’s Professionalism Award, is the Co-Chair of AAJ’s Jury Bias Litigation Group, and is a member of ABOTA and the American Society of Trial Consultants. They can be reached at jeff@boydtrialconsulting.com and nelson@nelsonboydlaw.com.

Jeff Boyd, Esq. & Deborah Nelson, Esq.

Boyd Trial Consulting Nelson Boyd Attorneysboyd@nelsonboydlaw.com jeff@boydtrialconsulting.com

nelson@nelsonboydlaw.com www.boydtrialconsulting.com

www.nelsonboydlaw.com 206.971.7601